Peace Alliance Winnipeg held its annual general meeting on April 12, 2025. This year’s meeting featured a keynote address by Manitoba author Owen Schalk entitled “Confronting imperialism in the age of Western decline.” Owen is a columnist for Canadian Dimension, the author of Canada in Afghanistan: A story of military, diplomatic, political and media failure, 2003-2023 and the co-author of Canada’s Long Fight Against Democracy with Yves Engler.

Posts Tagged ‘imperialism’

Confronting Imperialism in the Age of Western Decline

Posted: April 14, 2025 in Nibbling on The Empire, PeaceTags: imperialism, Peace Alliance Winnipeg, peace movement

Canada’s Long Fight Against Democracy

Posted: June 25, 2024 in Nibbling on The EmpireTags: Canada, Canadian foreign polity, imperialism

In this video, co-authors Yves Engler and Owen Schalk discuss their most recent book, one which reveals Canada’s foreign policy to be profoundly antidemocratic and in service to imperial and corporate interests. In their book, Schalk and Engler describe and analyze Canada’s role in the overthrow of twenty democratically elected governments between 1953 and the present day.

Yves Engler is a Montréal-based activist and author who has published 12 books and is a columnist for Canadian Dimension. In recent years Yves has sought to mobilize activists to confront politicians through peaceful, direct action. He has interrupted about two dozen speeches/press conferences by the prime minister, ministers and opposition party leaders to question their militarism, anti-Palestinian positions, climate policies, imperialism in Haiti and efforts to topple Venezuela’s government.

Owen Schalk is a writer from rural Manitoba. In addition to co-authoring Canada’s Long Fight Against Democracy, he is a columnist for Canadian Dimension magazine and the author of Canada in Afghanistan: A story of military, diplomatic, political and media failure, 2003-2023. He is currently working on his third book, which details Canada’s role in the 2011 NATO war on Libya.

This discussion was sponsored by Peace Alliance Winnipeg with support from CKUW-FM and the University of Winnipeg Students’ Association. It took place in The Hive at the University of Winnipeg on June 20, 2024.

Canada in Afghanistan – a conversation with author Owen Schalk

Posted: November 6, 2023 in Afghanistan, Nibbling on The Empire, WarTags: Afghanistan War, Canada, imperialism

PAUL GRAHAM: Owen Schalk is a writer of short stories, novels, political analyses, and essays on film and literature. He is a columnist at Canadian Dimension, and has written for Alborada, Monthly Review, Protean Magazine, and many other publications. His most recent book is entitled Canada in Afghanistan: A story of military, diplomatic, political and media failure, 2003-2023. It’s published this year by Lorimer and available online in paperback and e-book formats and at better bookstores across Canada. Owen’s book and what it says about Canadian foreign policy more generally is the topic of our discussion today.

Owen, and I’d like to begin by telling you how much I enjoyed reading your book. It’s well written and comprehensive. You provide an historical context for Canada’s involvement in America’s so-called War on Terror and it’s a context that most Canadians are not aware of and you bring to light many facts about Canada’s actions that thoughtful Canadians would find disturbing. So welcome. I’m really glad to talk to you.

OWEN SCHALK: Yeah, likewise. Thank you for the invite and thanks for that introduction.

PAUL GRAHAM: Let’s begin by talking about the scope of Canada’s involvement in the invasion and occupation of Afghanistan that began in 2003. What specifically did we do? Why did we do it, and what impact did our actions have in Afghanistan and for that matter, on Canada.

OWEN SCHALK: Yeah so in the book, I divide the military mission itself into four sections, and each section is represented by a major Canadian operation in Afghanistan. So I go through Operation Apollo – that’s from 2001 to 2003, then Operation Athena, Phase One, Athena Phase Two and then ending with Operation Attention. That brings us to 2014 and the withdrawal, and each of these operations had different tactics and aims, but taken together, they paint a picture of Canadian involvement that’s very wide-ranging. I mean, by the end, this mission cost us at least $18.5 billions. It involved ground, naval and air troops, special forces operations, psychological operations, development initiatives, domestic propaganda and more. These operations were embedded in a geopolitical context that saw Canada work with the US and work with NATO in Washington’s pursuit of a certain regional and global order.

So just running very briefly through these four operations that I used to structure the book, we begin with Operation Apollo which was Canada’s contribution to Operation Enduring Freedom – the actual invasion of Afghanistan. And that involved about 7000 Canadian troops working hand in glove with U.S. forces, and it ultimately involved almost every single part of the Department of National Defence. It was very, very comprehensive mission. And that that brings us to 2003, where we inaugurate the first phase of Operation Athena, which is based in Kabul.

And Athena Phase One is meant to support the goals of the ISAF in the capital. That’s the International Security Assistance Force and provide security for the new authorities as they organize elections for Parliament and President.

And so CIDA sets up offices during this time. The Canadian ambassador is welcomed back in a splashy ceremony. Thousands of Canadian soldiers are deployed to help set up this new this new constitution, the new elections, all of which, of course, excludes the Taliban and does not empower the true democrats in the country or those fighting for gender equality or economic equality. It’s designed to empower the Northern Alliance, which is this alliance of Northern warlords and militias, Tajiks, Uzbeks and Hazaras, who are for a lot of reasons opposed to the Taliban, which is Pashtun organization.

And Athena, in this phase involved police patrols, Canadian planners becoming tight with the new President, Hamid Karzai, influencing the new government’s economic policies toward a neoliberal orientation.

And it must be said, too, that the elections that Canada provided security for here were not exactly “free and fair” – to use the term that’s bandied about a lot today. The warlords were never disarmed, despite the population wanting that, knowing that intimidation would follow if they were not. There were reports of multiple voting and of course, foreign money, like US money, flowing to the winning presidential candidate, Hamid Karzai.

And that brings us to 2005, with the second phase of Athena, in which Canadian forces moved to Kandahar with the provincial reconstruction team.

And that’s really Canada most significant investment in the war. Once Karzai is entrenched in the capital, the Canadian forces relieve the US military from Kandahar, and they bring in what’s called a 3D approach, the defence development and diplomacy, but practically that means that the defence, the military component really, really dominates, and Canadian actions in Kandahar could be very heavy-handed, and they sowed a lot of distrust amongst the Afghan people there. It was really in Kandahar, where you see, like the big military operations – Operation Mountain Thrust, Operation Medusa. The development programs really get going with schools, health, education, the Dahla Dam, polio eradication: you know, very well advertised initiatives that were, in the end not successful if they were ever meant to be, but they did serve one important purpose, which was obscuring the fact that Canada was involved in this counterinsurgency war and not, as it was branded, a humanitarian peacekeeping mission. And that goes until 2011, when Canadian troops moved back to Kabul with Operation Attention, which is mainly a training mission that lasts to 2014 and then they withdraw.

So why did we do it? Why were we there from 2001 to 2014? And what impact did these actions have? I would say the reasons we were there have been very obscured by media censorship, on the one hand, and also propaganda. The military journalist David Pugliese says that this was the most extensive propaganda campaign designed to convince the Canadian public about the need for this war since World War Two and it was massive in scale. And the narrative that was forwarded at that time was that we were there to support human rights, to plant the seed of democracy and gender equality and the Real geopolitical interests, things like regional investment, the arms industry, the geopolitics: all of these things were not included in this narrative.

And what was the impact? I mean, all the major development initiatives failed. The Dahla Dam was never repaired, polio wasn’t eradicated. Canadian built schools often had few or no students. There were in some areas of the country for sure, life got easier for women, but Canada’s promotion of gender equality conflicted with the views of a lot of people Canada was supporting in the Karzai government. Like in 2009, Hamid Karzai endorsed a law legalizing rape within marriage and banning women from leaving their home without their husband’s permission. And this was Canada’s guy.

So, I guess to sum up this question, Canada dedicated a lot of resources to the occupation, but they did so out of material self-interest, the material self-interest of the state and they did not achieve much for the people of Afghanistan.

PAUL GRAHAM: When most Canadians think about Afghanistan, if in fact they think about it at all, they do tend to remember the military operations, the losses of life, of Canadians. Perhaps they even think about the many Afghan citizens who died in that conflict. But Canada’s role and you alluded to this a few minutes ago, was much broader than strictly a military one. They were participants in government in a fairly significant way. I wonder if you could talk a b it about that.

OWEN SCHALK: Yeah, of course. So, other than the military role, I think the most important aspect to consider is the economic one.

So at the time of the mission we were in that end of history moment as it was called after the Cold War, when Western leaders were telling the world that free enterprise and Western style democracy were the future. These models would inevitably spread, and that this was the end of any ideological conflict over economics. It would only be over culture from now on.

So the economic model that Canada supported in Afghanistan and around the world was a free market model, very neoliberal that reduced the power of the state and increased the power of foreign actors and international investors, including Canadian investors.

So I mentioned that during Athena Phase One, Canadian officials became very involved in the Afghan Government’s economic policy. There was actually a team of Canadian forces personnel called the Strategic Advisory Team – Afghanistan, the SAT-A, who were installed at the highest levels of the Afghan Government to advise on economic policy.

And they even helped write the Afghan national development strategy, which affirmed that privatization and the free market would be the guiding principles of the new Afghan economy.

So Canadian officers, they advised the economics team, they advised electoral officers, the president himself and the SATA was highly influential, like out of all proportion to their size. As part of this new economic model imposed on Afghanistan, we saw a lot of Canadian companies invest and secure lucrative, lucrative contracts.

In the country we saw mining companies pour in, engineering firms, consultants and more.

We can also say more about the development side of things – like the these aid initiatives that were so well publicized and celebrated. In reality, they were mainly photogenic, not concerned with the actual development of the Afghan economy. And at the same time that we had these development initiatives furthering a certain narrative about the mission, we also had Canadian companies coming in and they were the ones who were doing well off of this occupation. It wasn’t the Afghan people themselves, by and large.

So yeah, the military component was the most visible. It was the most talked about, but the economic dimension and foreign aid – those are also useful lenses through which to examine the mission and to understand the actual mechanisms by which it operated.

PAUL GRAHAM: Canadians have gone to war in faraway lands many, many times since Confederation, either as part of the British Armed Forces or as allies of American empires throughout the 20th century. And despite that, most Canadians tend to view our role of the world to be that of peacekeepers. In your book, you talk quite a lot about the gap between the myth of Canadian foreign policy and the reality. I wonder if you can expand on that a bit.

OWEN SCHALK: Yeah. So the myth of Canadian foreign policy is something I think all listeners will be familiar with. It’s the myth of Canadian generosity in international affairs, the idea that Canada’s sole interest around the globe is promoting democracy and human rights. And this myth has helped to craft a national brand for Canada this benevolent brand I think you could reasonably call it Canadian exceptionalism.

But in the book I attempt a deep history of how this brand emerged, going back to 1945, when Canada really started to spread its influence around the globe. And then I also look at 1947 and the Gray Lecture of Louis St. Laurent, where he kind of founded this idea that Canadian foreign policy is first and foremost concerned with moral questions, not economic ones.

And this this discourse of morality still infuses conversations around Canadian foreign policy, and it certainly did during the war in Afghanistan as well. But throughout Canadian history, there’s always been another thread that gets neglected if we accept that moral framing. And that’s the material thread, the economic thread, the question of what the Canadian state’s actual material self-interest might be around the globe.

So, I argue in the book that it’s always been about access to markets and access to resources. Going back to the post World War 2 moment and to Canada’s first foreign aid program, which is called the Colombo Plan, we see it there too. The explicit goal of the Colombo Plan, which was centred around Southeast Asia, was to fight communism and to encourage those post colonial nations to adopt pro capitalist reforms rather than socialist or Communist ones.

And Keith Spicer, this longtime government insider, he said that the primary motivation behind this aid plan was to stop these countries from replicating the Chinese revolution of 1949, which was a revolution that deprived Western nations of access to China’s resources on the West’s terms.

So that’s the reality of Canadian foreign policy, I would argue. Canada, like other nations, is motivated by economic self-interest and as a capitalist state, that means that Canada’s interests are capitalist interests: the spread of open markets, the ability of Canadian companies to invest on favorable terms to extract enough profit to make those investments worthwhile.

And frankly, I think it should be common sense that Canada has these selfish motives in its engagement with the world.

And yeah, we can go back to more recent wars that Canada participated in with Korea, Vietnam. That was mainly through arms production, not so much boots on the ground. The former Yugoslavia. There’s always a self-interest there. Material and economic self-interest. The fight against communism or, you know, the arms industry interests, the promotion of Western Power. It’s always there.

But self-interest runs counter to those myths of Canadian history, so it’s usually ignored in mainstream discussions of our foreign policy, including with Afghanistan.

PAUL GRAHAM: Can we dive a little bit deeper on some of these economic and commercial interests, particularly as they pertain to Afghanistan. Are there companies or industries that benefited in particular from that particular war?

OWEN SCHALK: I mean, yeah, totally. So we could talk about like the mining companies, there’s the major mining concession, the Hajigak mining concession in Afghanistan, which was the largest iron mine in the country and supposedly one of the largest untapped iron ore deposits in Asia.

And after the invasion, a Canadian company got part of that. There were, you know, many other companies, financial companies that were advising the Afghan government on their policy. There were engineering firms that benefited from contracts including SNC Lavalin and then arms companies, of course, in Canada that I detail in the book. These economic and commercial interests were very real and they were there for anyone to see.

And really, you could you could pick any area of the world, and if you do your research, you’ll see how Canadian corporate interests play a huge role there in shaping our government’s foreign policy. It could be the Caribbean, Latin America, Africa, Asia.

And absolutely the same was true of the Afghanistan mission.

And once you accept that that’s the logic that governs our states decision making, it becomes clear why Canada would involve itself in this war and to the extent that it did. You know, much like the Colombo plan, the war in Afghanistan and the War on Terror more broadly, as it was called, was about spreading a certain economic model around the world for the benefit of Canadian companies, and it goes without saying that these companies are deeply entwined with the state, with the major political party.

And undoubtedly that influences Canada’s international positions as well. But yeah, you could look at all these different sectors. I mainly focus on mining in my work outside of this book.

But I was able to find many examples of Canadian companies in various industries profiting from this invasion of this occupation.

PAUL GRAHAM: Former Prime Minister Jean Chretien had a particular interest in Afghanistan, did he not?

OWEN SCHALK: Yes. Jean Chretien flew multiple times to Turkmenistan to meet with the Turkmen President, President Niyazov, and he was there accompanied by Canadian oil companies.

And the Turkmen oil, was it played a huge role in the Afghanistan invasion and the geopolitics around it. You know, it was in US interests, Western interests generally, to see a pipeline of Turkmen oil flow through Afghanistan and into Pakistan and India. This was the TAPI pipeline.

And Chretien took an interest in that after he left the Premiership and yeah, he flew to Turkmenistan. He met with Niyazov, he was with these companies and yeah, Canada was very aware of this pipeline plan. They backed it in numerous meetings. The Defence Minister, Peter Mackay, said that Canada would defend the pipeline from Taliban attacks if needed. So yeah, absolutely oil. Another another key sector here.

PAUL GRAHAM: So, the shooting has stopped. The United States finally withdrew. The Taliban have regained control of the country, and presumably peace has come to Afghanistan, but the misery continues. Can you talk about how Canada and the United States and perhaps other countries continue to make life difficult for the Afghan people?

OWEN SCHALK: Yeah. So, in in early 2022, after the US had withdrawn from Afghanistan, the Biden administration chose to seize the new Afghan government’s central bank reserves, which were valued at a total of $7 billion, which is in a huge amount for any country, but especially in underdeveloped country like Afghanistan. And the situation worsened immediately, to the point that 95% of Afghans are not getting enough to eat. And meanwhile, Biden ignored calls to return that money to Afghanistan, leaving international charities and organizations trying to pick up the slack and bring the Afghan people some much needed assistance.

And Canada is implicated in this as well. And in a really shameful way. So while the Afghan people were struggling to eat, you know, also last year there were reports of hospitals filling up, soaring child malnutrition, people selling organs on the black market to survive. While all this was going on, the Canadian government policy was actually blocking aid from being allowed into Afghanistan.

And in August last year, World Vision had to cancel a shipment of food that would have fed almost 2000 Afghan children because of a federal law that bans Canadians from doing business with the Taliban, and that extends to aid in Ottawa’s mind.

There were reports of Canadian officials warning aid groups not to pay drivers to deliver food around Afghanistan, because that might give taxes to the Taliban, and this was as these groups were telling Western governments that they had warehouses full of food sitting inside Afghanistan that they couldn’t deliver because they might be penalized for it.

In the situation now, I haven’t been following it as closely. I know that earlier this year that Trudeau government said that they were going to reform these laws to allow an aid loophole. I haven’t seen much follow-up reporting on that. I was contacted earlier this year by a woman from Whistler who said that she donated to a charity that builds playgrounds in Afghanistan.

She had spoken with the people who run it. She was confident that they would be able to work there.

So it’s possible that Canadian government is loosening some restrictions a little bit.

But as for the situation improving anytime soon, I’m not hopeful. I mean, basically the entire population has been pushed into poverty and precarity, and it seems like the Western powers are keen on keeping Afghanistan frozen in that crisis. I don’t know if it’s indifference or if it’s vindictiveness over losing the war, but it’s hard for me to see that situation improving in the near future.

PAUL GRAHAM: Well, I guess geopolitically what one of the one of the reasons – and you go into this in the book – one of the reasons for the American invasion and the occupation had to do with controlling that part of the world and controlling energy resources – the transit of natural gas and oil, and depriving Russia and China of influence over the area. Is it possible that this continues to be part of the motivation for making life difficult for the Afghans?

OWEN SCHALK: Absolutely, that’s possible. I know that China has expressed interest in investing more in Afghanistan. You know, as part of this BRI [Belt and Road Initiative] project – to try to bring Afghanistan into that which would certainly bring more money into the country, [and] potentially alleviate some of the suffering there.

But yeah, I mean you mentioned kind of the geopolitics of this invasion and that that was a huge part of it. There’s a big concern in the US government at this time about any other country ascending to the point that it could rival US power. And in that region, Central Asia, South Asia, the main concerns were Russia and China rivaling US interests there, and Iran more of a regional power, but a lot of concern about Iran, especially because they were forwarding this plan of building a pipeline to Pakistan and India.

And of course, as I mentioned before, the US and Canada, they wanted Turkmen gas to go to Pakistan and India because Turkmenistan is a lot more friendly to the West than Iran is and they wanted to keep Pakistan and India friendly to the West because of this larger geopolitical game that I alluded to between the US and China and Russia. A lot of geopolitics involved here. And Afghanistan. Yeah, it has won its war against its occupiers, but it remains ensnared in this global game.

I don’t see the situation improving a whole lot anytime soon.

PAUL GRAHAM: You’ve co-authored another book that’s going to be coming out in 2024 with Yves Engler. Can you tell us a little bit more about that?

OWEN SCHALK: Yeah. So that book is called Canada’s long fight against democracy, published by Baraka Books. It’ll be out in February of next year. And that book is a history of military coups that Canada has supported. I believe it’s from 1951 to the present, and we found over 20 coups or coup attempts that Canada has either passively or actively supported. And there are also examples of Canada disregarding internationally monitored elections that don’t serve the state’s geopolitical interests. We have a chapter on the 2006 elections in Gaza, which obviously is very relevant to this moment.

And there are many examples that illustrate the capitalist and the pro corporate logic that determines Canada’s foreign policy decisions. One of the clearest to me is one of the actually the least known, which was a coup in the 1950s in Colombia that brought General Rojas Pinilla to power. Lester B Pearson was a big ally of Rojas Pinilla because he was saying, oh, he’s gonna buy Canadian fighter jets, so we should recognize him. He didn’t care what he was gonna do with those fighter jets. He just said, oh, this guy was a military dictator who came to power in a coup. We like him because he’s gonna help Canadian companies.

And we found evidence of this again and again. Guatemala, Congo, Chile, Uganda, Russia, Bolivia. Venezuela – so many examples and so much data that backs up our argument about the nature of Canadian foreign policy.

And I think it complements my Afghanistan book well too. You know, these are both books that have as a goal kind of the demystification of Canadian foreign policy, an effort to squint through the fog of nationalism and propaganda and censorship to glimpse the real inner workings of the state.

And Yves is one of the best people to read on Canadian foreign policy. I still can’t really believe that I wrote a book with him, but I think anyone who enjoyed my book on Afghanistan, they’ll get a lot out of this book too.

PAUL GRAHAM: Well, I could hardly wait until it comes out and maybe we can have you and Yves on.

So, you are a keen observer of Canadian foreign policy. In your view, what should we expect from the Trudeau government between now and the coming election?

OWEN SCHALK: More of the same, I would guess. I mean, watching events in Gaza right now has been truly sickening and disheartening to me to see the conduct of the Trudeau government there – supporting this genocide that we’re all watching unfold.

There’s another event of relevance going on right now that also kind of exposes how Trudeau views the world, and that’s happening in Panama. It’s not very well known, but in Panama right now, there’s a wide range of social movements rising up against a Canadian mine owned by First Quantum Minerals.

And that mine has been a focal point of social tension for years, and Ottawa has always backed the company against this range of protesters coming out to demand greater equality and more economic security for the country’s people and Trudeau has said nothing.

So I wouldn’t expect too much of a change. I think we might see – and I may be wrong – we might see a drift toward a less warlike stance in Ukraine, but if that happens, that will be a byproduct of the US losing interest in prolonging that war. I mean, there’s a recent article on I think NBC about how the US is urging Zelensky to maybe start considering peace negotiations or a compromise of some kind. But that’s of course in the context of what’s going on in the Middle East. So we might see a change there, but I could be wrong. Overall, I think the character of his foreign policy will remain the same as it has throughout Canadian history – that very pro corporate, self interested stance.

PAUL GRAHAM: Any final thoughts about your book or anything else?

OWEN SCHALK: I just encourage everyone to keep reading about Canadian history, about foreign affairs and Canada’s role in the world. There are many scholars who work hard to demystify this national brand around Canada and to get to the heart of foreign policy.

And I hope everyone keeps reading and I hope that my book can contribute in some small way to that growing catalog of really critical work on our foreign policy decisions.

PAUL GRAHAM: Well, thanks very much, Owen. Listeners, who want to find out where to purchase this book can go online to Amazon or to Indigo books or for a more complete list can go to Lorimer books at https://formaclorimerbooks.ca/product/canada-in-afghanistan.

And I guess we’re going to be continuing our conversation later on this week at McNally Robinson booksellers in Winnipeg, and I’m looking very looking forward to that very much. (November 10, 2023 at 7:00 pm)

OWEN SCHALK: Absolutely. Me too. And thanks again for the invite, Paul.

PAUL GRAHAM: And thank you. We’ll see you soon.

Winnipeggers mark the 50th anniversary of the Chilean coup

Posted: October 7, 2023 in Human Rights, Nibbling on The EmpireTags: Chile, Human Rights, imperialism

On September 11, 1973, Popular Unity Government of Salvador Allende was overthrown in a violent coup d’état carried out by the Chilean military with the backing of the government of the United States. The coup leader, General Augusto Pinochet, implemented a bloody campaign of torture, imprisonment and murder. Thousands were killed; thousands more imprisoned; perhaps 200 thousand more were forced into exile. Several hundred found a safe haven in Winnipeg, Canada.

These political exiles, along with friends and supporters in Winnipeg, came together at the Franco-Manitoban Cultural Centre on September 11, 2023 to remember those dark, terrifying days from half a century ago and to honour the many brave men and women who resisted Pinochet’s tyranny. Here is the video I recorded of this commemoration.

Making Sense of World Events

Posted: March 16, 2023 in UncategorizedTags: capitalism, imperialism, political economy

Making sense of world events is always a challenge. Corporate media reports are usually superficial and misleading, lack historical perspective and are hobbled by ideological blinkers that prevent alternative, critical analyses from surfacing. While alternative voices exist, you won’t find them in the corporate-owned mainstream media because, as the late A.J. Liebling wryly observed in a 1960 article in the New Yorker, “Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.”

Liebling died before the Internet was a thing and hence can’t be blamed for not anticipating the explosion of low-cost publishing platforms that enable people of all persuasions to challenge official narratives. This. of course, introduces other challenges – who to listen to and where to find them, to name two. I don’t have a satisfying answer to these questions and propose only to add to the confusion. To paraphrase Orson Wells, “I don’t know anything about politics, but I know what I like.”

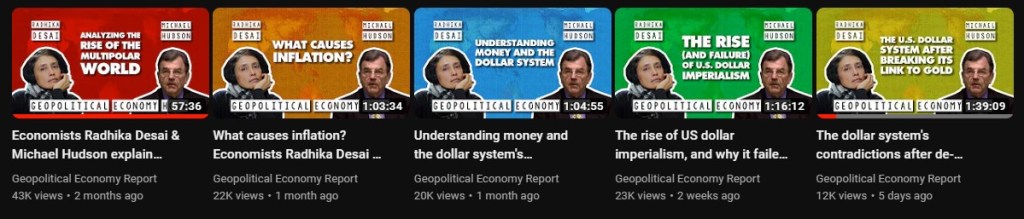

With that in mind, allow me to introduce a new. bi-weekly program I have been editing since very recently, entitled “The Geopolitical Economy Hour” that appears as a regular feature on Ben Norton’s YouTube Channel, the Geopolitical Economy Report.

The GEH features two of my favourite thinkers, Professor Radhika Desai, a co-founder of the Geopolitical Economy Research Group at the University of Manitoba and Professor Michael Hudson, President of The Institute for the Study of Long-Term Economic Trends.

To date, we’ve produced five episodes and you can look forward to many more that promise to go beyond the headlines and reveal the root causes of the political, economic and social upheavals we are witnessing and experiencing.

I recommend that you add this program to your list of reputable sources of information and analysis.

Canada’s ongoing betrayal of Haiti

Posted: November 13, 2021 in In Solidarity, Nibbling on The EmpireTags: Canada, colonialism, Haiti, imperialism

In this webinar, viewers discuss the film Haiti Betrayed with director, Elaine Brière, and the current Haitian situation with activist Jennie-Laure Sully. The webinar was hosted by Peace Alliance Winnipeg on Nov. 13, 2021.

Background

In 2004, Canada collaborated with the U.S. and France to overthrow Haiti’s elected president, Jean Bertrand Aristide, who enjoyed widespread support among the poorest Haitians. Since then, with Canada’s support, a series of right-wing governments have overturned Aristide’s reforms and violently repressed his supporters.

Released in 2019, Elaine Brière’s documentary, Haiti Betrayed, exposes the role Canada played in the 2004 coup. You can watch it here, in English or French.

Biographies

Elaine Brière is a Canadian filmmaker and photojournalist. Her first documentary, Bitter Paradise: The Sell-out of East Timor, won Best Political Documentary at the l997 HOT DOCS! festival and Production Excellence award at Seattle Women in Film in l998. Bitter Paradise aired on TVO, CBC Radio-Canada, CFCF-12 Montreal, BC Knowledge Network, SCN, WTN, PBS and Swedish National Television.

The Story of Canadian Merchant Seamen, released in 2006, aired on SCN and Knowledge Network and toured extensively in New Zealand, the UK and Australia.

Elaine’s photographs have been collected by the visual arts section of the National Archives of Canada. Her work has appeared in The Globe & Mail, the New York Review, Canadian Geographic, Carte-Blanche, and the Family of Women. East Timor, Testimony, was published in 2004. She is the founder of the East Timor Alert Network and received the Order of Timor-Leste in 2016 for her contribution towards the liberation of East Timor from Indonesian occupation.

Her current feature documentary, Haiti Betrayed, on the role of Canada in the 2004 coup d’état in Haiti, was released in late 2019. It was translated into French in the summer of 2020 and aired on TV5 in Québec and France.

Jennie-Laure Sully is a researcher at the Socioeconomic Research Institute (IRIS) and a community organizer at CLES, a center for sexually exploited women.

She studied anthropology and public health and has a master’s degree in biomedical sciences from the University of Montreal. She has worked as a research coordinator in hospitals and as a psycho-social caseworker in rape crisis centers.

Jennie is very active in the women’s movement and in the movement for the human rights of migrants. She was born in Haiti and moved to Quèbec with her family when she was 2 years old. Among the many causes she cares about, the fight against imperialism and for the sovereignty of Haiti is among her top priorities.

The New Cold War, Canadian Foreign Policy and Canada’s Peace Movement

Posted: March 7, 2021 in Act Locally, Nibbling on The Empire, Peace, WarTags: Canada, imperialism, Peace, War

On Feb. 27. 2021, Peace Alliance Winnipeg hosted a webinar entitled “The New Cold War, Canadian Foreign Policy and Canada’s Peace Movement.”

It featured presentations by:

Radhika Desai, a Professor at the Department of Political Studies, and Director, Geopolitical Economy Research Group, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada. She is the author of Geopolitical Economy: After US Hegemony, Globalization and Empire and numerous other books and articles on political and geopolitical economy and world affairs.

Yves Engler, a Montréal-based activist and author who has published 11 books on various aspects of Canadian foreign policy. His latest book is titled House of Mirrors — Justin Trudeau’s Foreign Policy.

Tamara Lorincz, a PhD candidate in Global Governance at the Balsillie School for International Affairs (Wilfrid Laurier University). She is on the board of directors of the Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space and on the international advisory committee of the No to NATO Network. She is a member of the Canadian Voice of Women for Peace and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

The webinar was moderated by Glenn Michalchuk, chair of Peace Alliance Winnipeg.

While the quality of the presentations was first rate, the audio quality of Radhika Desai’s presentation was less than optimal. Don’t let that dissuade you from listening. What she has to say makes it well worth the effort.

GET INVOLVED

If you feel inspired to get involved in changing Canada’s foreign policy for the better, here are some organizations that could use your energy.

Surviving the decline of the American Empire

Posted: November 19, 2019 in Nibbling on The EmpireTags: economy, imperialism, Michael Hudson

July 21, 2019: Professor Michael Hudson gave the final keynote at the 14th Forum of the World Association for Political Economy, held in Winnipeg at the University of Manitoba. Photo: Paul S. Graham

Michael Hudson is President of The Institute for the Study of Long-Term Economic Trends (ISLET), a Wall Street Financial Analyst, Distinguished Research Professor of Economics at the University of Missouri, Kansas City, author of many books and an outspoken critic of capitalism.

He spoke at the 14th Forum of the World Association for Political Economy, held in Winnipeg at the University of Manitoba this past July. The theme of the conference was “Class, State and Nation.” Professor Hudson’s talk, which I’ve titled “Resisting Empire” (because YouTube likes short titles), charts the rise and decline of the American Empire and some of the strategies implemented by other nations (principally China) to overcome the domination of the United States.

What follows is video I recorded of his talk and (for those who prefer to read) a transcripts of his remarks, lightly edited for clarity.

I can’t think of a conference where I’ve learned so much starting with the wonderful three-hour tour of Winnipeg and the general strike in 1919. It’s sort of a metaphor for everything that we’re describing in the world today. That here you had a city that had the potential to be taking off. They talked of it as a potential Chicago. And what happened? The workers and the general strike wanted the same things that workers all over the world have wanted. They wanted higher prosperity. They wanted a decent pay. Shorter hours would have been more productive.

And yet the ruling class of Winnipeg, the Thousand said, we, we could have a wonderful growth. We could make a lot of money in real estate alone by immigrants coming here. We could make it a centre , but then other people would have to get rich just like we are. We don’t want it. We would rather be relatively rich and keep them poor than have development. We want to keep our status of control over them so that we have all of the initiative, all of the planning power and they are powerless because that is for us the system.

It’s not an economic system. It’s the same system that existed in Rome. And the result of course is that Winnipeg didn’t become another Chicago. It became Winnipeg today.

Well, this same attitude is the attitude that the United States is taking towards the rest of the world. And the question is, will, the rest of the world be more successful than the Winnipeg strikers were in 1919?

From the very beginning, I’ve been a part of WAPE (World Association for Political Economy) and the very first issue, volume one, number one David Laibman and I had an article. So, we’ve been part of this for a long time. Uh, I want to thank both Radhika and Ellen for the wonderful organization of this meeting.

I did write a paper for it that maybe will be posted. But after listening to the discussions here, I’ve decided to make a different set of comments. And I think the framework for my comments is that capitalism has not evolved in the way that Marx expected.

Marx wasn’t wrong, but he was an optimist. He thought that capitalists would act in their own self-interest. Well, of course, if they would have acted in their self interest, you wouldn’t have had the Winnipeg general strike. He thought that their interest was going to be in becoming more efficient in streamlining the economy and getting rid of the fictitious costs, what he called the false costs or full fray of production. And he’s rightly been called a revolutionary. But what upset the vested interests more than anything else was not simply that Marx is a revolutionary, but that he showed that capitalism itself was revolutionary. He said the historical destiny of capitalism was to get rid of the landlord class that simply collected rent without providing any productive service. The task of capitalism was to get rid of parasitic finance and instead finance would be used to fund industrialization as it seemed to be happening in his time in Germany and in central Europe. And he thought that the role of capitalism was to be so much more efficient that in a speech he gave before the Chartists in London, he supported free trade, not on the basis of the neoclassical and neoliberal silliness of free trade is being productive.

But he said, well, the one virtue of free trade is going to be that since Britain is the most efficient economy its trade with India is going to break down all of the backwardness of India. And as British manufacturers undersell the manufacturers of countries that are backward, that have elites that have predatory and parasitic vested interests and ruling classes, they would have to either modernize or be swept away. And it seemed logical to him that capitalism would pave the way for a natural evolution into socialism by at least getting rid of the carryovers of feudalism the landed invasions, the warlords that became the Lords and controlled the politics and the land.

Well, as we all know, that’s not what the leading economy of the United States is today. If Marx were looking at the United States, he wouldn’t say, I think that it’s wonderful that all the other countries should follow the United States lead because it’s going to bring about prosperity and efficiency. In contrast to England and the industrial revolution, the United States has become the most inefficient economy in the world in terms of manufacturing. The reason that there cannot be a revival of a manufacturing industry in this country is simply because the accumulation of debt has gotten so large and the price of housing and the privatization of monopolies and health insurance has become so expensive that if American workers were to get all of their food, all of their clothing, all of their transportation for nothing, for zero, they still couldn’t compete with China or even Europe because out of every paycheck they have to pay up to 40% of their income for rent. 15% is taken off for social insurance and medical care, another 10% for payments of interest and debt.

Only a small portion of the worker’s budget is available to be spent on the goods and services they produce. So the United States is left in a very high cost position and has become something that is different from the industrial capitalism that Marx talked about in his day. Industrial capitalism has become finance capitalism and the roots of finance capitalism, the basic analysis for it is all outlined in Marx’s volume three of Capital and volume two. The reason he left it for volume three and volume two and not in volume one was he thought that there was already the 1848 revolutions in Europe; already there was pressure to tax away of the rent of the landlords. Already there was pressure to create a public subsidy of health, of basic monopolies of post office, of transportation, and communication.

And by the time Marx wrote, he thought, okay, that fight has been won. Capitalism can take care of the post feudalism problem. And Marx talked about the problems of capitalism itself, the relationship between the employer and the employee. And for him, industrial capital was money that was spent on employing labor to make a profit and squeeze out surplus value.

This seemed to be the way that the world was evolving until World War One and World War One really changed all of that. England found itself bankrupted by the debt that it owed to the United States when the war was over. For hundreds of years, Europeans at the end of a war had simply canceled the mutual debts because they thought we’re all in it together. But the United States said, well, we sold you a lot of arms before we were in the war. So we’re really not brothers. You have to pay us enough money that to cause mass unemployment there — to essentially do to England what the IMF has done to the Third World after World War Two. And so England and France also had to pay into her ally debts turned to Germany to pay the reparations and caused austerity and a crisis in Germany. And the result of course was a chronic depression that a build up of debts that finally all had to be wiped out in 1931, 1932, when the inter allied debts and reparations were forgiven. And the crisis was so great that it brought on the world depression of the 30s that was only pulled out by World War Two.

So, what has happened since World War Two was something that Marx could not have expected. He thought that banking and finance capital would be industrialized. He described finance as external. Finance existed in Babylonia in the third millennium BC. Interest bearing debt was in Rome and Greece. But all of this debt Marx described was simply parasitic. It took money and it accumulated and it grew by the mathematics of compound interest. And Marx collected everything that was written in his day on the mathematics of compound interest. And he said, it grows inexorably by purely a mathematical laws of its own power and there’s not part really of the capitalist system, but if the banks made productive loans to industry where the bank credit provided the industrial borrower with the means of earning a profit, able to repay the debt, then that would become productive. And that would become a basis that even socialism could apply.

Many of Marx’s followers in the 19th century expected the banks to be the planning center, the incipient planning center of the socialism to come. And this view was based largely on the German experience where there was a combination of the Reichsbank, the large banks the military for credit for armaments, especially for the building of navies and heavy industry. And it was largely a government coordinated development in Germany, which seemed to be headed towards the leadership of the world.

This terrified England because England really had failed to do what seemed potentially able to do in 1848. It wasn’t able to get rid of the banks by the time that in 1914 when World War One broke out, there was a set of articles in the economic journal in England worrying that England was going to lose the war because its financing was so predatory, so greedy, so corrupt and its behavior was so short term hit and run that it could not possibly compete against an economy that had basically planned productive credit as a Germany had. The stockbrokers in England were notorious for putting their customers into financial frauds and just hitting and hitting and running, for taking over companies and insisting that the companies pay all of their income out as dividends, not reinvest their profits, not accumulate productive power, but rather simply build up debt. And the Marxists were in the lead of describing this phenomenon of finance capitalism that at the time it seemed to be a perversion of industrial capitalism, but turned out to be something almost entirely different. And we all know the result of that.

That was World War Two. And in World War Two, the United States set out to dominate the world and make itself the center, sort of a wheel and spoke system. The United States called this globalization or internationalism.

But the role of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund was not internationalist at all in the spirit that we just heard describing the Belt and Road Initiative. The idea of the World Bank was not to promote development, but to promote dependency. The leading assumption of the World Bank was under no case would domestic currency loans be made to develop agricultural self sufficiency and countries to become independent and grow their own food. From the very beginning, the United States wanted loans to go only to the export sector. Third World countries, Latin America, Africa, the Near East were told to depend on American grain and the loans were only for export crops to build railroads and roads to lower the cost of making exports so that America could get raw materials from other countries.

And America became [what it] accused England of wanting to make it in the 19th century — hewers of wood and drawers of water. That was how the Bible phrased it. So you know, what has happened as a result? Well we had a dependency system here. At the time America emerged from World War Two, it had by far most of the gold supply of the world. And at that time the domestic money created by central banks with based on gold. The United States had such a dominant possession that by the time the Korean war broke out in 1950, the United States had accumulated 75% of the world’s gold supply.

This meant that other countries were facing austerity. The Americans expected quite correctly that as a result there was going to be rising social revolution in these countries. So the American free market planners realized the first premise of free market economic theory — I don’t know why this is left out of the textbooks that they teach — the first premise is you cannot have a free market unless you’re willing to assassinate everyone who opposes you, unless you can have a regime change for any country that does not follow a free market. All of Roman history is this. The fifth fourth, third, first century BC. Every single advocate of debt cancellation, of land redistribution, of democracy, was killed. The United States immediately set up a regime change in Guatemala overthrowing the Arbenz government that wanted land reform.

And it came in, in support of British Petroleum in Iran and overthrew the elected Mosaddegh regime. And it installed dictators throughout Latin America long before you had Pérez Jiménez in Venezuela. You had everyone there. Kissinger was very open in backing Pinochet in Chile saying if you have an opponent of free markets — meaning American dominated — you’re free to buy anything you want in the United States, but you have to buy it — whatever you buy — in the United States. He said we have to kill, not only the leader, but the entire class. And the result was a huge 10-year war throughout all of Latin America, political assassinations of labor leaders, of socialists, of academics, of professors — a mass of terrorism.

And it was really in the 1970s that America emerged as the leading terrorist country in the world backing its concept of free markets and democracy. By democracy. It meant pro American. Any regime including the Ukrainian Nazis that are pro American are called a democracy. Any country no matter of whether they elect their leaders or not is called anti-democratic or totalitarian, meaning other than the United States.

So, the problem is: where can we go from here? Well, the problem of finance capitalism is finance is extractive: leveraged buyouts, stock buybacks, finances short term. Banks look at something [as] “how much can we collect?” And banks don’t lend in terms of “what can our loan create in productive capacity to earn the profits to pay?” They say, “if we make a loan, where is the property that we can grab when there is a default?” The aim of creditors throughout history has not been primarily to earn interest. It’s not to earn interest. It’s to foreclose and get the property of the debtors that cannot pay the interest. This is essentially the IMF’s policy, in a nutshell. It will make loans to countries as long as they’re in the US orbit. It will not make loans to countries opposing the US and it makes loans in conjunction with World Bank plans that cannot be paid. And when there is a balance of payments crisis of countries IMF’s clients, they’re told “you can pay us by selling off your property, by privatizing your property, privatizing your mineral resources, privatizing your public utilities, and your natural monopolies, especially your electric companies, your water companies your oil reserves.”

This is the game and the IMF essentially is the knee-capper, as we say in America, it’s the gangster for the American objective of buying out control of other countries. Because we’re in a position now which Alan Freeman has pointed out where we’re not growing in the United States. And if you look at the actual growth in GDP, all of the growth in American GDP since 2008 has only gone to the top 5% of the American economy, Wall Street, the finance, insurance, and real estate finance sector. The 95% of the economy is shrunk. And if you say, well, what is this GDP growth? Well, one big element is late fees charged by banks on debtors that can’t pay. When banks charge a late fee the GDP economists say that’s providing a service of taking a risk to provide the economy with credit.

The other maybe 8% of the GDP is the increased value of homeowners’ homes. In other words, they’re asked, if you own your home, what if you had to pay rent for your home? How much rent would you have to pay? And as housing prices are inflated on credit the houses price goes up, the rents go up more and more. And so this increase in GDP is the increased value of homeowners’ living conditions, even though it’s the same home. No new home has been built, nothing has changed except the inflation of housing prices. So basically, what passes for GDP growth in the United States is simply the increased asset pricing the inability of labor and industry to pay debts, causing late fees, and what the classical economists called unearned income, economic rent.

So, we’re a rentier society and America’s relationship to the rest of the world is that of a rentier, that is a rent extractor. It lives off the interest and the property that it can grab as a result of its international credit. It lives off the dollar standard, a free ride. After America went off gold in 1971, countries had to keep their foreign reserves in some kind of risk-free asset. And the only risk free asset large enough was the US dollar. And the reason there were so many US dollars in the world is they were pumped into the world economy by means of the balance of payments deficit. Now, balance of payments deficit: that sounds abstract, but in practice, the entire deficit, every cent from the 1950s, 1960s onward, it was military and other, the private sector is just about in balance, but the America through its 800 military bases over the world, and its supply of dirty tricks and the American foreign Legion is very expensive.

The foreign Legion is ISIS, Al Qaeda and the other terrorist groups. So all of this is creating a huge influx of dollars and these dollars end up by the free market being spent largely in China, Asia and other countries and America, until about a year ago, said you countries can earn as much as you want by running your own balance of payments trade surpluses, but you have to send all of your surplus to the United States by buying US treasury bonds to finance, not only the US budget deficit, but to finance our expenditure on encircling you with our 800 military bases. That’s called a circular flow, and that was the definition of equilibrium that they had. Now, you can imagine my surprise a few months ago when Donald Trump came out and accused China of manipulating its currency by buying US treasury bonds.

And Trump’s argument was — somehow, he read an economics textbook — this was a disaster. He was very successful being a petty criminal throughout his life. He made his money by not paying his workers, by not paying his suppliers. He’d go to suppliers, offer 50 cents on the dollar and say, well, if you don’t like it, sue me. And in the United States, it costs about $50,000 to mount a court case to collect. And he ended up cheating people. He didn’t pay the banks. He defaulted. No bank in the United States will lend to Donald Trump. No contractor in New York city, where I live, will deal with him. No labor will deal with him. He thought that it worked for him; it will work for the United States. All you have to do is promise the moon which is called equilibrium I guess for economists and then say, well, here’s what we’re going to pay you.

It obviously is not working, but this puts other countries including China in a dilemma. What is it going to do with all of the dollar payments that it gets from other countries in Asia, in the Third World and the United States ? What will it do with them? Well, a few years ago, it said, well, the natural thing for us to do is what the United States does. We will recycle these dollars by buying up foreign industry. They tried to buy oil, not just filling stations. Oil distributors in America. America said, that’s a national security threat. There was a discussion in Congress. They said, anything China owns that makes them richer is a threat to our national security. Well, this is just what was said in Winnipeg in 1919. Any improvement in the status of labor or to anyone but us is a threat to our security and our domination.

So, China is considered a threat to our national security by being prosperous. This is not a case of the most efficient economy in the world spreading its way of production into other countries. It makes other countries essentially colonies. It’s a form of financial neocolonialism. And the advantage of neocolonialism in a financial means is you don’t have to draft an army. In fact, the whole character of control has shifted away from military. The last draft in America was in the Vietnam war, and if America tried to invade Venezuela or any other country you would have the same kind of riots in America that you had during the Vietnam war. So that’s why America needs either a Foreign Legion or what’s called client oligarchies like it’s trying to install throughout Latin America and for other countries.

But you have to sort of feel a little sympathy for America’s position. And I want, I want to make a plea for sympathy. How can this country survive if it can’t be permitted to kill your leaders? If it can’t be permitted to take over your industry and get all of the rents and the profits and the raw materials for free? How on earth can it survive if it can’t produce its own industrial goods? It’s high cost. It’s heavily indebted. How on earth are American companies and the employers and the employees who worked for them that are heavily indebted — pension funds will lose their money, the stock prices will go down, the banks will go bust, there will be defaults on the real estate. So America really feels that the only way that it can survive is by international sabotage.

The only kind of war that a democracy can afford to fight is by bombing. It can’t afford to have a military draft, it can’t afford to invade a country because of the domestic politics. It can only bomb. It can only destroy. That is the only form of warfare that is available right now. So what is amazing is the lack of response by Europeans. All of this has been celebrated since about 1980 as the end of history. And this end of history book came out right after the Soviet Union dissolved. And that was taken by America to say, well, we’ve won. The end of history means there is no alternative and they’ll make sure there is no alternative because American policy is to make sure that history will not change, that there won’t be an alternative to the current way of doing, of doing things.

So, this is not survival of the fittest. It looks like it’s the survival of the parasites. It’s the survival of an unproductive, predatory economy. And if you’re making a forecast about the future, the natural tendency is to assume that everyone will act in their self interest and everything will grow better and better. But that’s not happening. If you looked at Rome, exactly the same thing happened in Rome. Finally by the first century, there was such a land grab, such a monopolization of land, such a power of creditors. Revolution after revolution uprising after uprising — everybody expected Caesar to cancel the debts. And he was killed by the oligarchy for wanting to be even, even moderate. The result of what then was neo-liberalism, meaning the vested interests are in control, was the dark age in feudalism.

So, the question is whether the American plan, the neoliberal economics, is going to lead to a new kind of feudalism and how other countries can protect themselves. Rome survived for a century by looting its more productive richer provinces like Asia minor and Gaul. But finally, there was no more money to loot and the economy just collapsed from within. And in a way, this, this problem is inherent in Western civilization. It made Greece and Rome different from Sumer, Babylonia, Persia, the Near East. All the Near Eastern countries, when they had a debt problem, the rulers, would step in and cancel the debts and they would reverse all of the land transfers. Where people had lost their land to the creditors, the land would be returned to them. Every single ruler of Sumer and Babylonia in the third millennium and second millennium did this. This became the Jubilee year of the Bible, which was taken over word for word from the Babylonian lawyers. It remained in force in Constantinople, the Eastern Christian empire, but not in the West.

The West has the concept of progress and this ideal of progress is irreversibility. You can’t go back. This is the problem that president Obama faced himself with. He’d promised to write down the debts of the junk mortgage loans of the fictitious loans, and keep the homeowners in their houses. But then he said, no progress means you can’t cancel the debts. You let the debts completely go up.

No member of the 1% will lose their money. That means the 99% has to lose their property. And President Obama invited his Wall Street backers to the White House and said, I’m the only person standing between you and the mob with pitchforks. These are the people that Hillary Clinton called the deplorables. The role of the American president was basically to convince the population that somehow all of this neoliberal stagnation that they’re experiencing is all for the good. And you’ll have the economics profession sort of looking at all of history this way.

All of you have heard about Rome falling into the Dark Age, but there is a new economic history of neo-liberals. It said, well, it wasn’t so dark. If you look at the rich people, there were a lot of big manors. And there was a lot of trade and nice ceramics, all Near Eastern. All the traders were Near Eastern. All the money that Rome could extract from its colonies was sent to India or further East. But they say that the rich people had such an enjoyable life that we really can’t call it a dark age. It was only a dark age for the 99% of the people. And but look at the 1%, you know that’s what we have in the museums. Was it all worth it or no?

So the question is, what does China do in response to all of this? Well, obviously the first thing it’s doing is agreeing with Donald Trump. Yes. We’re going to de-dollarize. We’re certainly not going to keep our savings and loans to the US treasury that enable you to encircle us with military bases. So de-dollarization is one aspect.

China’s not going to ask the International Monetary Fund the planet’s economy and tell it what industry is to be privatized and sell off to private managers who will simply increase the prices that China has to pay for its electricity, transportation and others. So, and in fact, it’s set up its own independent bank as a by-product of the Belt and Road Initiative. It has its own bank and its bank is financing actual tangible investment instead of financing dependency. In response to the unilateral us trade war and protectionist tariffs, China has the option of countervailing sanctions. The United States already has large investments in China. The balancing factor would be for China to say, okay, you’ve grabbed our money. We’ll just take what you have here and call it even.

There’s obviously a cyber war. Also, as you know, the American CIA and national security system have worked with Silicon Valley to install back doors so that it can spy on every other country. What makes China’s Huawei so undemocratic is it doesn’t have spyware for the United States. And so that obviously is a threat to US control. So you have that in place of the class war and the austerity program in the US China’s kept its credit in the public domain.

This means that in America, when the company — you’ve seen the wave of bankruptcies of American corporations recently, especially in the retail sales — when an American corporation goes out, a hedge fund or a vulture fund comes in and buys it at a fraction of the cost. In China, there are many industrial plants that have been unable to pay the debt, but because the creditor is the government, the bank of China can simply write down the debt. It writes it down so that it keeps the industrial employer in business. It doesn’t sell it off to a hedge fund or an American. China realizes what Marx expected to be the future for banking and finance. It’s a public utility. It’s created electronically, basically credit. Any bank can simply make a loan and create money.

China’s already doing that, and the final capstone is that China’s developed an alternative economic theory to neo-liberalism and that’s Marxism. Marxism looks at the overall context. It places it in the context of politics so that it looks at the economy as a system, not as parts to be carved up and essentially looted. So, as long as China can continue to develop its monetary policy, its trade policy, its foreign policy and military policy, in keeping with this overall view of systemic growth, it’s going to be operating in a way that creates its own future instead of passively surrendering to America’s neoliberal future.

Winnipeg solidarity with Chile, Bolivia and Venezuela

Posted: November 17, 2019 in Nibbling on The Empire, WinnipegTags: bolivia, Chile, imperialism, solidarity, Venezuela, Winnipeg